Is the Church, Now, a Non-Place?

Yi-Fu Tuan describes in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience the organization of society during the Middle Ages. This description is simultaneously an historical understanding of how cultural and social (and financial) power flowed through built communities and the romanticized ideal of what the modern—and relevant—church wants to represent in contemporary society.

Architectural space reveals and instructs. How does it instruct? In the Middle Ages a great cathedral instructs on several levels. There is the direct appeal to the senses, to feeling and the subconscious mind. The building’s centrality and commanding presence are immediately registered. Here is mass—the weight of stone and of authority—and yet the towers soar. These are not self-conscious and retrospective interpretations; they are the responses of the body….There are the countless signs pointing to Christian doctrine, practice, and mystery: holy water, flickering candle light, statues of saints, confessional, pulpit, altar, and cross are examples….the Cathedral as a whole and in its details is a symbol of paradise. The symbol, to the medieval mind, is more than a code of feelings and ideas that can readily be put into words. The symbol is direct and does not require linguistic mediation. An object becomes a symbol when its own nature is so clear and so profoundly exposed that while being full itself it gives knowledge of something greater beyond.1

The question, then, is: does the church in form and function maintain its sacral architecture and socio-cultural import? Or put differently is there any basis to maintain the nostalgic view of the church as a reality in a Capitalist-captured world?

It doesn’t take much to reckon with a physical difference between modern and the medieval. Just look around. Within urban and metropolitan places, the eye is directed towards the skyline which constitutes the central mass of the city. Yet even the rural towns and villages have become reconstituted within modernity. It is common to travel through a Midwestern town of a few thousand and see a “town square” at the center—symbolically, if not physically—of the communal built environment. There are differences in density, to be sure, but the “downtown” and the “town square” still signal the same things. They signal where the hub of business and often governance takes place. The churches, while they might be near those dense masses of commerce, are not physically or—as will be argued here—symbolically central to our modern societies.

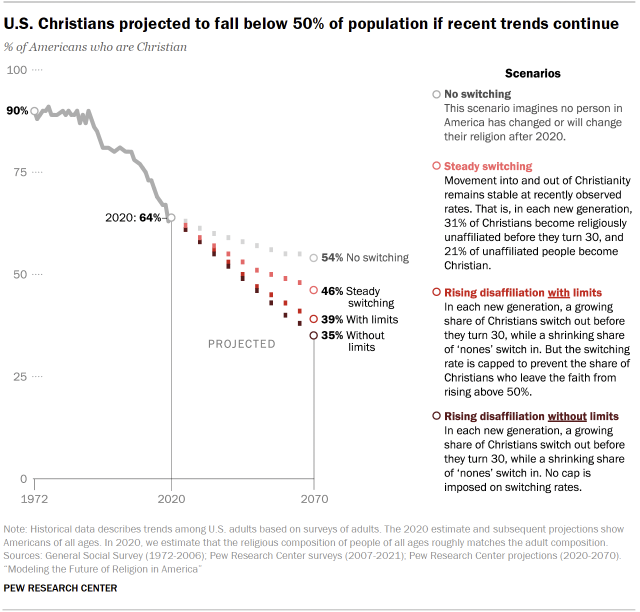

And statistics seem to show—as much as they have the ability to accurately show—that there seems to be a downward trend in individual Christian belief and the collective visibility of the religion itself.

With a modest awareness of urban and rural surroundings and a quick web search of stats, it is not hard to find that the built presence of the church, visible and invisible, in this romanticized medieval idealism has been displaced by commerce and governance for they are at the center, physically and, seemingly, symbolically, of the modern landscapes.

Yet, is the church a “non-place”? This is a different question altogether. The term “non-place” was brought into popularity—at least within leftist political circles—by Marc Augé in Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity. In the Second Edition introduction to the 2020 reprint by Verso, Augé speaks of a “triple decentring” within modernity. The first of these speaks to what has already been described here, the movement from historic centers of society (like the church) to commerce and industry. Yet he moves on to two increasingly more intimate de-centerings:

In the dwellings themselves, houses or apartments, the television and computer now stand in for the hearth of antiquity….The individual, finally, is decentred in a sense from himself. He has instruments that place him in constant contact with the remotest parts of the outside world….The individual can thus live rather oddly in an intellectual, musical or visual environment that is wholly independent of his immediate physical surroundings.2

Augé goes on to breakdown what he constitutes as a non-place within what he calls supermodernity. By non-place, he is speaking to “spaces of circulation, consumption and communication.”3 He is speaking to a new regime of spaces that contain people, but people do not leave social inscriptions of community or culture in or on them. The airport, supermarket, the mall, and other spaces where people enter and exit to do business or to be transported elsewhere. These are spaces that have been created and/or modulated by these factors of social and individual de-centering.

So we go back to the previous question: is the modern Christian church in America a non-place?

The question is too complex to completely parse out here and will be a subject that I will return to, more than likely, again at a later time. However, there are some observations that can be postulated towards an answer to the question.

Simply put, cathedrals just are not built any longer. They are too labor-intensive and materially-expensive to build and risk/reward index is low on profitable returns. Notice I intentionally couched my reasoning in economic terms. This is because economics (with a political façade) constitutes the linguistic language of our day. Common sense contains the constraints of the economically-profitable. (Side-note: this is in part why STEM programs and science are the drive of our age, because they are the tools of industry and technology which is where profit is made. Meanwhile, humanities lie half-paralyzed on the side of the road waiting for the next vehicle to end their misery forever).

Instead, the architectural style of the modern church becomes economically cost-effective. So, instead of building with the intention of sacral form and function—its appearance “teaches” as Tuan puts it and it cultivates time for the surrounding community by the rhythms of its religious rites and teachings—the modern church builds metal boxes with efficient façades of exterior insulated finishing systems (EIFS) or fiber cement or metal paneling systems. Or churches hole up in the commercially haunted strip malls of the suburbs or outer extents of the city (often highly industrial centers).

Those churches that find themselves inheriting those old cathedrals or their more austere Protestant cousins do so without the ability to maintain the building as is needed or to use the space effectively. For there is no actual need to use it since the church itself no longer instructs or is the focal point of the modern American society. Instead, they must focus on feeding their flocks of individuals—who enter the space, fill the space for a while, and then leave that space to tendril out into their separate repositories of residential developments and work—and seeking to extract enough money from these individuals to maintain the building and the staff. This sounds cynical, but in a consumptive society, extraction is simply a means to an end. The work of extraction is not always intentional, but instead the only way to maintain any kind of presence for the church in a society that has de-centered it from their communal life.

It seems like the church has become a non-place, not of its own choice and not completely of its own doing, but because Capitalism has won. The mythical free market and the standards of eternal economic growth have displaced it from the central concern of community. The community has been splintered and deconstructed by technology into groups of individuals that fill a space for a time, but seldom inscribe any collective meaning on those places they inhabit. Duty to others has been displaced by rights for the individuals. Communal meaning has been replaced by the nuclear family and the ongoing abstraction of “attainment.” Tithing, a duty done because of the love of the Creator, is transformed into another means of economic extraction so that the place and those who carry the fire of the good news can continue to subsist on the outskirts.

It is the confluence of capital, radical individualism, and this new guard of abstracted “places” we live thanks to our smartphones and computers that I fear makes the modern Christian church—at least in America, probably in the world—a non-place. Those who still attend to the good news of Christian doctrine carry the light into these non-places and hope for a transformation by the work of the spirit that hovered over the empty void of creation. The hope in all of this is that the great commission of Christ demands that we carry His presence even into the non-places of this world.